Riding the coattails of a decades-long mezcal and tequila boom, an array of new and newly popular Mexican spirits are exciting aficionados and compensating for years of hard work on the part of promoters and producers. Both ancestral concoctions like pox or sotol as well as distillation experiments in gin and whiskey are suddenly front and center in bars across Mexico as well as north of the border.

You can’t be faulted if you haven’t heard of some of these, but you will be left behind if you don’t get into the mix. So here are a few Mexican spirits you should know and some places to try them for the first time.

Pox: Ancestral drink of the Tzotzil

Hailing from the southern state of Chiapas, pox – pronounced posh – is believed to descend from a drink the Tzotzil Maya people made from fermented corn over a century ago. Potent and alcoholic, today’s pox is made from a blend of corn, wheat and sugar cane, with good pox including a dominant percentage of corn and an AVB of 40 or above. In a good pox you will notice the sweetness of the piloncillo sugar and the strong flavor of the endemic corn used to make it. Pox is one of the least publicized spirits in this list, used for generations in religious rituals of the area’s Indigenous people and as a homebrew medicine. Only recently has pox started to make its way out of the rural mountain regions of Chiapas and into local bars committed to showcasing the vast array of Mexico’s regional spirits.

If you’re seeking a taste of this time-honored elixir try San Cristobal de las Casas restaurants La Tarumba or Tierra y Cielo, where you can find cocktails with local pox, or a bar like Rayo in Mexico City where pox is blended with Maestro Dobel Diamante Tequila, purple sweet potato, lime and palo santo as one of their 10 signature cocktails. To buy your own bottle, try woman-owned and operated Poxna, a brand out of Chiapas sold at the Sabrá Dios liquor store in Mexico City and their San Cristobal tasting room La Espirituosa.

Charanda: Not your average Cuba Libre

Charanda, which comes from the state of Michoacán, has an official appellation of origin, meaning that its methods of production and distillation are both regulated and protected as intellectual property — nothing can be called charanda that doesn’t meet certain parameters. Often compared to rum, Michoacan’s charanda has special attributes: the high-altitude sugar cane varieties it’s made from have greater sugar levels than its lowland cousins and the area’s mountain spring water gives the region’s spirit a distinctive flavor.

When producing charanda, additional sugar or piloncillo is added to the fermenting sugar cane juice, distinguishing this process from that of traditional rum. Charanda can be divided into three categories, the unaged blanca, the medium-aged dorado, and the darkest and most mellow, añejo, which is often aged in bourbon or sherry barrels that provide it with additional flavor complexity. Charanda can be enjoyed similarly to rum — Cuba Libre, anyone? — but for something a little more elevated, El Gallo Altanero in Guadalajara serves up the Duranzo Mojado with two types of charanda, peach, falernum syrup, grapefruit, sweet lime juice, orange liqueur and black pepper. Uruapan, the birthplace of charanda, is home to La Charanderia, where you’ll find one of the widest selections of quality charanda in the country.

Raicilla: The underground mezcal making a comeback

Makers of raicilla will let you know right away that this liquor is a type of mezcal — much in the same way that tequila is a type of mezcal — but that raicilla is made from specific types of agave in a handful of municipalities in Jalisco and Nayarit states.

As opposed to mezcal production, in which only the hearts of agaves are cooked and mashed for fermentation, in some raicilla production, every part of the agave is included. This gives those varieties a more fibrous flavor, often less sweet and more woody than mezcal. During the colonial era, the Spanish outlawed the production of this kind of mezcal, so local producers “renamed” it raicilla and production went underground. Its big comeback moment came in the 2010s, when the consumption and sale of raicilla catapulted it onto the national stage.

Most raicilla is still produced 100% artisanally using hand mashers and only basic implements like copper stills in the distillation process. Raicilla has grown in popularity with the rise of mezcal and has its own appellation of origin for its region and production. For a taste at the source, try the La Taberna, which is the bar run by the Mexican Council to Promote Raicilla (CMPR) in Mascota, Jalisco, or try the El Cucumber cocktail at De La O in Guadalajara which is a blend of Raicilla Japo, lime, green chartreuse and orange bitters.

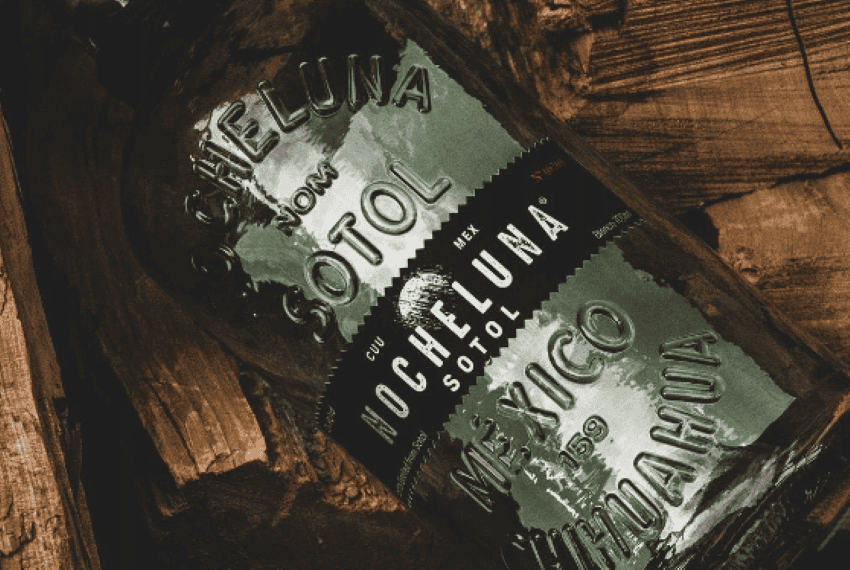

Sotol: Jewel of the desert

The corpse reviver at Cafe de Nadie in Mexico City blends Flor de Desierto Sierra sotol with “chinampa vermouth” (an infusion of vermouth, white wine, and herbs grown in the city’s southern canals), as well as Peychuad bitters and citrus oil for a taste that is refreshingly bitter and alcoholic. Sotol is often confused for mezcal, but its flavor profile tends to be a bit pinier and is often described as more herbal or citrusy. Made from the desert spoon cactus, sotol production is centered in the northern desert states of Chihuahua, Durango and Coahuila, but can also be found across the border in Arizona, New Mexico and Texas, though it is generally thought of as a Mexican spirit.

Its history dates back to the Indigenous people of the region, who made a fermented beverage with the desert spoon cactus plant, albeit minus the distillation process that arrived with European colonizers. The process of making sotol is similar to that of mezcal: the piñas, or hearts of the plant, are cooked in stone or earthen pits in the ground, then mashed and allowed to ferment for several days until being distilled — often more than once, depending on the profile sought by the sotol makers.

Bacanora: The outlaw that rose again

Bacanora is another style of mezcal produced in a cluster of southeastern municipalities of the state of Sonora that hug the border with neighboring Chihuahua. Made from a single plant – the Pacifica agave – bacanora is generally less smoky than mezcals from Oaxaca, has a greater minerality and a certain woodiness to it. Bacanora can also be distinguished by its yellow and golden hues in-bottle.

Bacanora’s history also dates back several hundred years, when the native peoples of the region made an alcoholic drink from the same type of agave. Its production was briefly outlawed in 1915 when the state’s governor, future president Plutarco Elías Calles, decided to crack down on illegal production of alcohol. The decision was reversed in the 1960s when the production of bacanora was reinstated and regulated and named a beloved regional spirit. Two excellent options for bacanora are Batuq and Los Amavizca. If you are in Mexico City stop by Tlecan bar and try a vampiro with bacanora, orange juice, a blend of chilis and salt.

Whiskey: Foreign and endemic come together

Whiskey is on the rise in Mexico, and while not a type of alcohol production endemic to this country, today’s producers are combining the unique characteristics of the 59 heritage corn varieties available across Mexico with the long-honored tradition of whiskey making born in Europe and brought to the Americas during the colonial period.

Some of the best Mexican whiskey I’ve tried is in Tlaxcala at the Cuatro Volcanes distillery, which has been making liquor with locally-sourced, small-production corn harvests since 2019. Their tiny distillery and cocktail bar is located in a residential area of Tlaxcala city, and, along with whiskey, they are experimenting with gin, absinthe, fruit brandies and other liqueurs made from local plants and fruits. In Mexico City, you can try many of their spirits at Fuego, which has a selection of all of the spirits in this article. If you want to branch out, a few other good options for Mexican whiskey are Juan del Campo, Origen 35 and Gran Tunal.

Fruit Brandies: Mexico’s newest trend

Mexican fruit brandies and liqueurs have just started to sneak onto bar shelves and cocktail menus. Many are made in regions where other spirits or wine are produced and used as a way to make efficient use of leftover fruit production or as an alternative to making mezcal when a harvest is bad or producers don’t have the money to purchase the quantities of agave they need. In these cases, they might turn to an over-abundant mango harvest, or in the case of Vinos Barrigones, a pandemic happenstance that found their mezcal distillery (located in the middle of a vineyard) with no mezcalero to lead it. They decided to make a pivot that resulted in the birth of their first brandy.

Brandies and liqueurs offer a wide range of flavor profiles depending on the producer and are an excellent showcase of Mexico’s expansive domesticated and wild fruit varieties, with tejocote (Mexican hawthorn), nance and prickly pear flavors as a few of the wilder experiments.

If there was ever a zeitgeist moment for Mexican distilled spirits, it’s right now. Greater visibility for all these liquors has made this an incredible time to start branching out into the wide variety of spirits, and a growing national cocktail culture has meant incorporating them into drink menus in new and inventive ways. For flavors that truly represent the land and people of Mexico, a regional spirit can offer you a taste that nothing else can.

Lydia Carey is a freelance writer and translator based out of Mexico City. She has been published widely both online and in print, writing about Mexico for over a decade. She lives a double life as a local tour guide and is the author of Mexico City Streets: La Roma. Follow her urban adventures on Instagram and see more of her work at www.mexicocitystreets.com.